Sound leaves no evidence. There’s no stain on the ceiling, no crack in the plaster — nothing you can point at and say there. An apartment can feel silent at noon and turn hostile at 2 a.m., when a bass note rolls through the wall, not loud enough to complain about, just loud enough that your body is now awake. Your jaw clenches. Not because the sound is dangerous, but because someone else — unknowingly — just decided how your next day is going to go.

For years I tried the usual arsenal — earplugs, white noise, therapy, bargaining with neighbors. Nothing worked. Actual silence is rare when you rent in a city.

Suffice to say, I did not jump to designing a soundproof sleep capsule right away.

Pillows on the Bathroom Tiles

My rage was selective. Wind didn’t bother me. But if a human made the noise — a hot spike of adrenaline.

I stopped trusting daylight viewings. Before signing a lease, I’d ask realtors to let me sleep there for a night.

One night stands out. I found a spacious apartment near a park that seemed perfect — until 11 p.m., when the building’s central heating pipes began to vibrate. A low, periodic hum seeped into the walls, the bedframe, my chest. I waited for it to stop. It didn’t.

Eventually I dragged my bedding onto the cold bathroom tiles — the only room without dedicated heating — queued a ten-hour “Brown Noise” track, and tried to convince myself this was fine. Looking from the toilet bowl to my pillow, I wondered how I ended up here.

The Half-Ton Hypothesis

If I couldn’t control the building, maybe I could control the boundary between it and my bed. The plan: solve this mechanically, once and for all.

Recording studios solved this decades ago. The question was whether I could get studio-grade isolation in a renter-friendly, bed-sized package. I grabbed the industry bible of studio construction, and immediately learned I had a lot of misconceptions.

My mental image was egg cartons and acoustic foam — the YouTube studio look. But that stuff is absorption: it reduces reflections and makes a room less echoey. What I needed was isolation: stopping my neighbor’s bass from reaching my pillow. Foam barely matters there; low-frequency energy just plows right through.

Bass was the target—the hardest to stop, and my main sleep problem. A bass note really does vibrate a cement wall. The amplitudes are nanometers, invisible, but enough: the whole slab rocks back and forth like a piston, re-radiating the bass on the other side. Higher frequencies I could solve with earplugs and closed windows.

To stop low-frequency waves, acoustical engineering offers only two expensive tools: mass and decoupling. Mass is brute force — a heavier wall is harder to shake, the same way it’s harder to push a parked truck than a shopping cart. Acousticians call this the mass law. Double the wall’s mass, and you gain about 6 dB1 of extra isolation — noticeable, but not dramatic.

There’s a deep unfairness in acoustics: making noise costs nothing, but stopping it costs a fortune. A neighbor’s footstep is free; the mass required to block it weighs hundreds of kilograms.

Decoupling is sneakier: you build an inner structure that floats free of the outer one, so vibrations lose their path. Hold a tuning fork in the air and it hums quietly; press it against a table and the whole surface becomes a speaker. Decoupling keeps the tuning fork in the air.

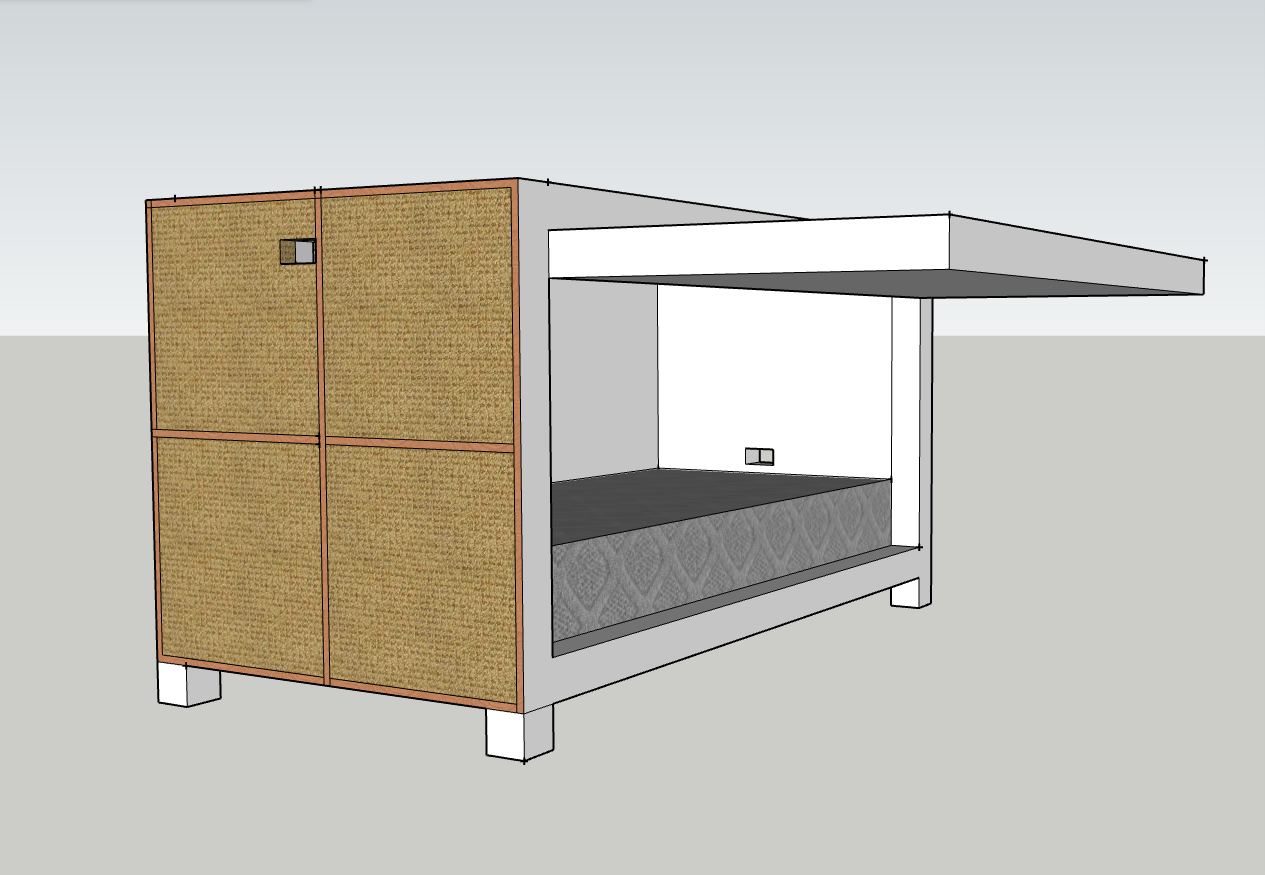

The canonical approach is a “room within a room.” In studios, the inner shell sits on rubber pads and doesn’t touch the outer walls, floor, or ceiling — a box floating inside another box. In my case, I thought: what if the inner room is just… bed-sized?

Once the requirements took shape, I hired Fehim — an engineer I found on Upwork — because I didn’t actually know how to design physical objects at this scale. The mass needed for real attenuation (reduction) pushed the estimate past half a ton.

A 100 kg door is not furniture; it’s a crushing hazard. In my sketch it was a rectangle. In reality it was a lever arm waiting to rip hinges out — or tip the structure.

You don’t just “hang” a slab of mass-loaded vinyl (a thin, dense rubber sheet) and plywood; you build a steel cage to contain it. The deeper I dug, the more obvious my ignorance became.

I’d assumed plywood, drywall, and mineral wool were “cheap.” They are, until you need a lot of them. Fehim pushed for a prototype first. I’d somehow become the “perfect on the first try” client, and he had to talk me into cutting scope. I’m glad he did.

No Uncutting a Board

Then I ran into a harder problem: air.

A sealed box is quiet. It’s also a coffin.2 The moment you add ventilation, you add openings—and sound treats openings like invitations. It floods through the tiniest crack.3

So the project stopped being “build heavy walls.” It became “build heavy walls and somehow let air in.”

Grime accumulation, emergency exit… Hermetic seal? A submarine CO₂ scrubber? My project folder kept growing. But everything else would matter only if I could get the walls right.

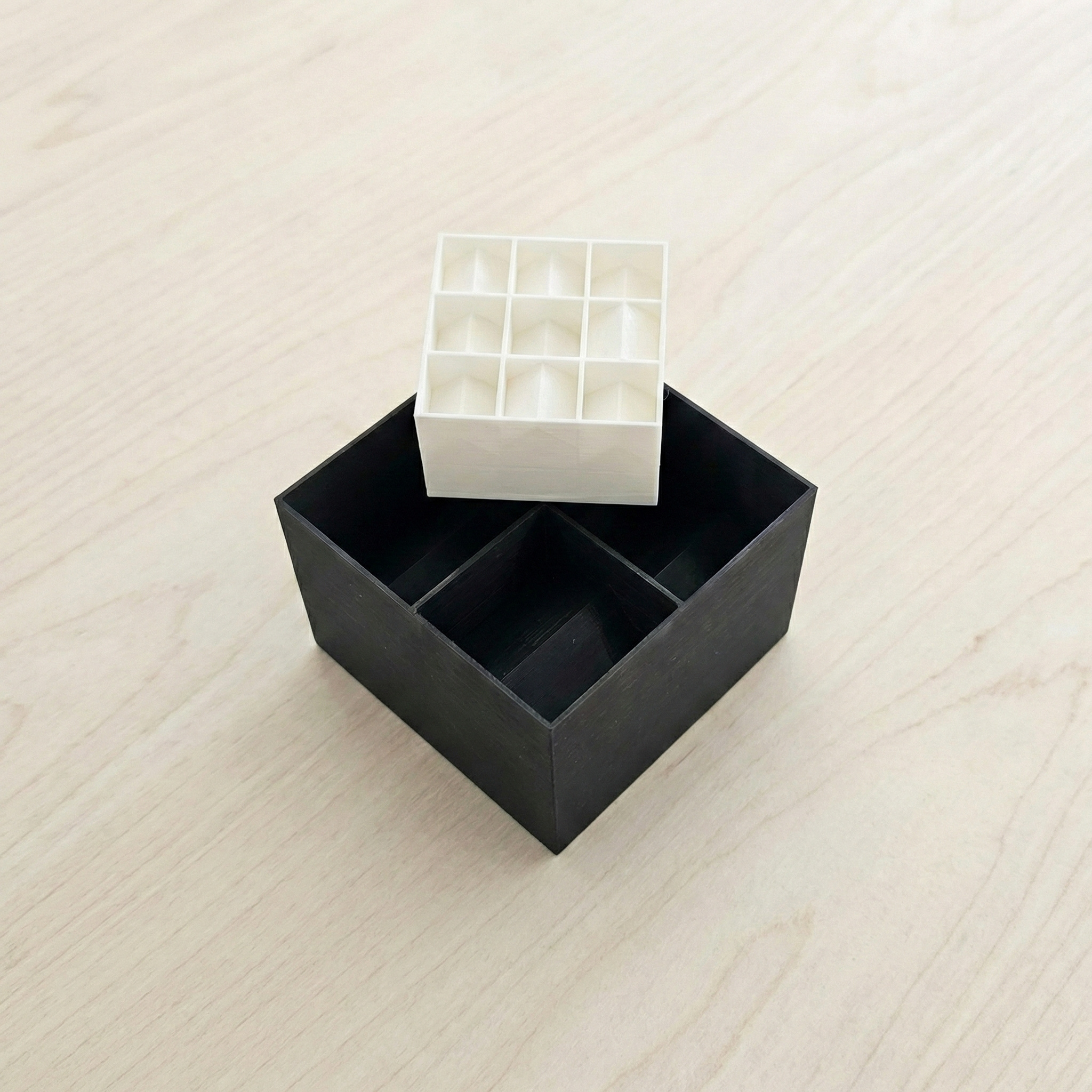

I started with basics: a half-meter prototype cube with heavy, decoupled double walls.4 I bought mineral wool for the cavities, but after realizing the hair-thin glass fibers would coat my apartment, I stuffed them with old clothes instead. The goal was simple — test whether mass + decoupling + sealing = real attenuation.

I didn’t have the tools, so I asked in a local chat. A stranger — Alex (thank you!)—offered his backyard and his workshop, helped source materials, and taught me a few saw tricks on the spot. Without him, the cube might’ve stayed a sketch.

I assumed a plywood cube would be trivial. Then reality showed up: blades have thickness, wood has knots, and tiny errors add up until your “square” box needs quotation marks. And every fix removes more material — there’s no uncutting a board.

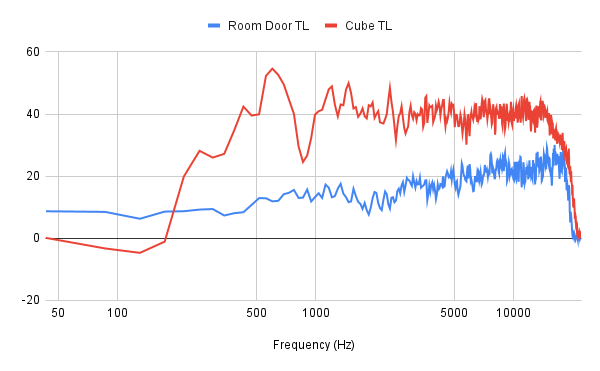

With the cube built, I set up a calibrated Dayton Audio mic and a flat-response speaker at 85 decibels (sound pressure level),5 played pink noise — a signal that hits every frequency at equal loudness — and recorded. Then I placed the mic inside the cube, played the same noise, and compared.

Subtract the two curves and you get the cube’s sound transmission loss (TL): how many decibels it blocked at each frequency. Everything above zero means the cube blocked sound. Below zero means it amplified it.

This wasn’t a lab-grade measurement — the test room had its own reflections and modes. But the result was unambiguous enough.

I wanted to slam the laptop shut.

At the low frequencies I cared about, the cube wasn’t just ineffective — it was ~10 dB1 worse than no cube at all. I’d built a giant guitar body: a resonance chamber that grabbed the bass and hummed along.

At first I blamed my construction, then my testing setup. Later, theory explained one of the dips: at certain frequencies, the sound waves bounced back and forth inside the cube at exactly the right spacing to reinforce each other — like pushing a kid on a swing at just the right moment. The cube’s internal dimensions were accidentally tuned to amplify the very frequencies I wanted to block.6 I never figured out the second, sub-300 Hz dip.

After that graph, I went into avoidance mode. For weeks the designs sat untouched, and “ambitious” started to feel like “delusional.”

In retrospect, the pivot to metamaterials was partly genuine curiosity and partly a refusal to sit with the failure. There’s a version of curiosity that’s genuine and a version that’s escape. I told myself I was pivoting to a better solution. I was also running from the possibility that there wasn’t one.

Thousands of Tiny Bottles

Eventually I went looking for a different lever — something smarter than “add more plywood.” That’s how I found acoustic metamaterials — materials whose behavior comes less from what they’re made of and more from how they’re shaped.

Jet engines can’t be sealed, so they reduce noise with honeycomb structures that act like thousands of tiny Helmholtz resonators tuned to eat specific tones. A Helmholtz resonator is simpler than it sounds: blow across a bottle top and you hear a note. That note is the air in the neck bouncing against the air trapped in the body, and the bottle absorbs energy at exactly that frequency. Change the bottle’s shape, change the frequency it eats. Now imagine thousands of precisely shaped “bottles” embedded in a wall — each one swallowing a different slice of the noise spectrum.

I read acoustics papers and kept running into the same seductive idea: attenuation without the weight. Could geometry replace some of what I’d been trying to purchase with sheer mass? One paper (Hedayati et al., 2024) had enough data for me to reproduce the build.

This led to a delightful detour into parametric CAD — design software where every dimension is a variable you can tweak, then regenerate the whole model. Unlike the cube, this could iterate without sawdust: tweak a dimension, regenerate, print again. I ended up designing and 3D-printing an array of Helmholtz resonators.

Holding the first print felt like a victory — until I did the math. To cover a capsule, I’d need hundreds. Filament cost and print time ballooned into months. I never tested a single one. The prototype now holds spent batteries on my shelf — a monument to parametric CAD, if nothing else.

The Last Paper

Then I found a paper by Krasikova et al. (2023) that captured my imagination. The authors used plastic plumbing tubes with cleverly cut holes to create paired Helmholtz resonators, and reported attenuation across a broad range. Most metamaterials target narrow bands (like a specific engine frequency), but my goal was broad attenuation. This paper promised exactly that — and claimed it didn’t even require a hermetic seal.

I emailed the author with clarifying questions (she replied!). Plastic tubes were light, cheap, and targeted the needed frequency range. For the first time in months, I fell asleep picturing the finished build — not cataloging problems.

After three months and six emails, I was ready to build. I opened a spreadsheet to finalize the Bill of Materials.

Each resonator tube needed a specific length to target a particular frequency. To cover a bed-sized enclosure — say, 5 meters of perimeter and 1 meter tall — I’d need six resonators per block, eight blocks per meter of wall. The sum at the bottom of the column stared back at me: 250 meters of PVC.

I’d optimized for “lightweight” while ignoring “how much.” The resulting structure would still weigh over 500 kg, but now it would be made of thousands of glued tubes instead of simple plywood. I’d spent months on acoustic metamaterials only to arrive back at the same brute-force truth: mass laws are non‑negotiable.

I closed the spreadsheet and, for the first time, didn’t open another paper.

The Door Slammed at 2 a.m.

When a recurring problem disappears without you changing anything, you don’t relax — you brace for its return.

My sleep improved, though I never isolated the variable. Recently a door slammed at 2 a.m. I noticed. I rolled over. A year earlier, I would have stayed awake, jaw clenched.

Maybe Finland’s lower ambient stress finally settled into my nervous system7. Or maybe the act of building — even building things that failed — gave back what I’d actually lost: not quiet, but agency.

I disassembled the cube, reclaimed the plywood, and reused the CAD skills on my next hobby project. In total I spent under 1,000 euros — about 300 on the engineer, the rest on materials and tools — and a solid month of full-time effort. None of it produced silence. All of it mattered.

Sound leaves no evidence. But the sawdust did.

-

Decibels are logarithmic. 6 dB means roughly four times the sound energy, though your ears perceive it as only a moderate change. 10 dB is about twice as loud subjectively. ↩ ↩2

-

In a sealed capsule roughly 2 m × 0.8 m × 0.8 m (about 1.28 m³), a sleeping adult exhaling ~0.2 L/min of CO₂ would push concentration past 1% — the threshold for headaches and impaired cognition — in about 2.5 hours. Past 4–5% you risk unconsciousness. Any real build would need forced ventilation, which means holes, which means sound leaks. The leaks are solvable with a baffle box — a zigzag channel lined with absorptive material that lets air through but forces sound to bounce and die — but designing one that moves enough air quietly is a project in itself. ↩

-

Even a tiny gap dramatically undermines isolation — an opening of just 0.01% of a wall’s area can halve its effective sound blocking. ↩

-

Outer walls 45 cm, inner cavity 20 cm. Each outer wall was two sheets of 15 mm birch plywood. Inner and outer shells were decoupled with Gyproc XR 95 resilient channels — thin metal strips that flex, so the inner wall doesn’t rigidly touch the outer one. The old clothes likely reduced high-frequency absorption compared to mineral wool, but shouldn’t have affected the resonance problem, which was driven by cavity geometry. ↩

-

Measurement rig: EarFun UBOOM L speaker (chosen for its flat frequency response — important so the test signal doesn’t favor any pitch), Dayton Audio iMM-6 calibrated measurement mic, placed 1 m from the speaker at 85 ±3 dB SPL. Recorded in Audacity; TL graph generated with a Python script using the mic’s factory calibration file. ↩

-

The inner cube was 170×200×200 mm. Two acoustic modes collided at 857.5 Hz — one of the valleys on the graph. ↩

-

Moved there in 2024, before starting this project. ↩